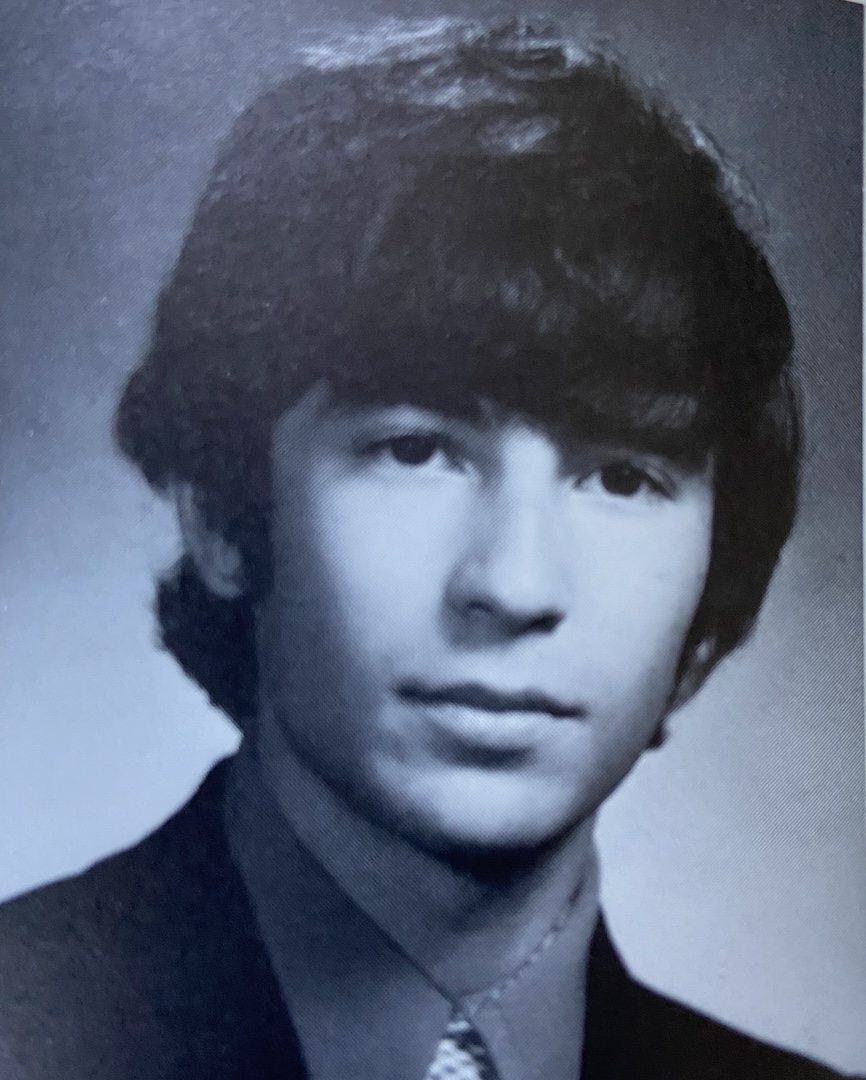

In high school, Michael Small was the kid who did everything. Decades later, he’s still taking on opportunities to share others’ stories while learning how to hold on to his own.

When Small was a Masconomet senior in 1975, he was involved in everything from athletics to the arts, and welcomed a busy and well-rounded high school experience. While many students were counting down the days until graduation, Small found joy in staying present and making the most of every moment.

“I had an unusual experience at Masconomet because I just loved it, and I’m not sure everyone felt the way I did,” he said.

Instead of treating his high school days as something to escape, Small embraced them as something to cherish. Without a rush to grow up, he held onto the experience, knowing how rare it is to feel such a belonging at a young age.

“One of my strong ideas in high school was focused on being at Masconomet. Do not think about going to college or your career, or getting out. This is where you are. Make the most of it. And that made me have a good time,” he said.

Like most public high schools in the 1970s, Masco had its cliques, athletes, artists, and, as Small put it, “hoods.” But he was one of the rare individuals who had a foot in all these groups, serving as a connector rather than an outsider.

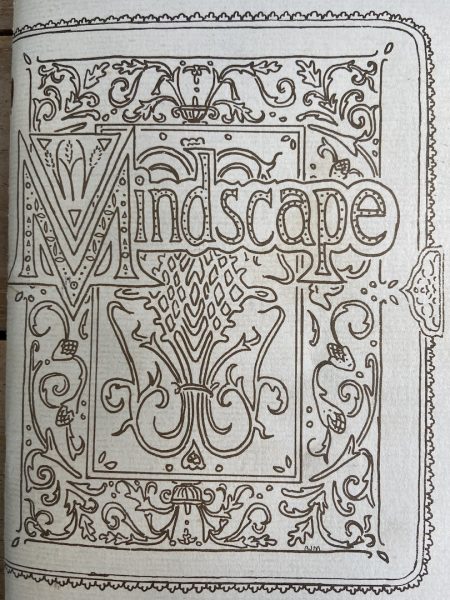

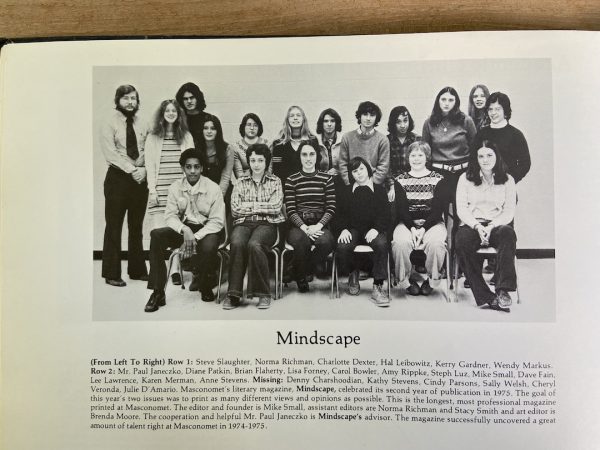

“One of my favorite things was to go to people in all those different groups and try to get them to write for the literary magazine. So I would go to the sports people and try to get them to do sports stuff.”

That openness, paired with his distinctive and self-deprecating sense of humor, made Small quite approachable across social groups.

“I was this really nerdy little guy who could easily be beaten up or made fun of, and it didn’t happen,” he said. “And part of the reason why I think I got away with it is that I really like to laugh, and I like humor. And so nobody could really make fun of me because I’d make fun of myself first.”

He used the literary magazine, Mindscape, as a bridge to create a community, inviting people from all groups to contribute. To Small, it wasn’t just about writing, or a grade, or building a resume, it was about making people feel seen and valued, regardless of their “label” or group.

“I learned that even in a small environment like Masconomet, there are many different types of people, and it’s worth getting to know all of them.”

Small went on to attend Harvard University, yet another formative experience where he learned the importance of diverse perspectives and the power of connecting with others. He majored in history and literature, which were classes he hadn’t explored as a high schooler, but which became central to his developing identity in Cambridge.

“If I had a good experience at Masconomet, I had a freaking amazing experience at Harvard. I had fantastic teachers off the charts, and I had fantastic friends, and it was so luxurious. The room was beautiful. Everything was great,” Small said.

At Harvard, students participate in a tutor program where a faculty member works closely with students within their major. Small recalls his tutor, who had a photographic memory and pushed him to expand his thinking by challenging his ideas and holding him to a high standard.

“She had the ability to analyze things and change my thinking and make my mind work in a different way. And her comments usually were longer than my paper, but she taught me how to write. And so through history and literature, I learned how to express my ideas clearly, and I used that in journalism. And that was a huge help to me.”

Years later, Small found himself returning to that same creative dynamic while working in digital media at Entertainment Weekly and Wired magazine; just like how he used to run Mindscape in high school, he was once again building a team, assigning roles, editing content, designing layouts, and applying the leadership skills he first developed as a teenager.

“I worked on one of the very first websites for Wired magazine. And I created Entertainment Weekly magazine’s website and ran that for almost 10 years. I was learning the technology of how to do it better, which was exactly what I did for Mindscape in high school,” he said.

With over a decade of experience in digital media and website design, these roles allowed Small to expand his technical skills and provided him with the unique ability to connect audiences with content across platforms. This naturally led him into journalism, where his curiosity about different social groups shaped the path of his career.

“There were two reasons [why I decided to go into journalism]. One that sort of relates to Mean Girls, which is, I really wanted to meet the hoods in Masconomet. I really wanted to meet the jocks. And I wanted to hear what was on their mind. I could just go to anybody and ask them any question I wanted and find out more about their life and who they were,” Small said. “I mean, what could be better than that? There were no limits. You could go ask anything you wanted.”

Driven by the desire to understand people from all different backgrounds, Small found journalism to be the perfect outlet for his curiosity. With the freedom to ask people introspective questions, allowing for candid and intimate conversations, he built trust through storytelling, but remains rooted in the ethics of his profession.

“When you are interviewing people, you don’t become their friends. You have a very friendly time. It seems like you’re friends. You’re not friends. You’re doing your job to pretend to be friends,” said Small.

Even though he often formed meaningful connections during interviews rooted in open and vulnerable exchanges, he emphasized the importance of professionalism and respect. He said the best way to keep connections strong was by fact-checking thoroughly and following up with kindness.

“Always write thank you notes,” a Page Six journalist once told him, advice he carried with him and practiced throughout his career.

“So I wrote thank-you notes to people, and they were not expecting that. And when I saw them the next time, they were more likely to give me an interview when I needed a follow-up interview. They were open to me.”

That sense of care soon defined the way he interacted with sources. During his 12 years at NBC News and MSNBC, Small witnessed reporters spending hours verifying every detail of their work to ensure accuracy. With appreciation for those rigid standards, he highlighted that fact-checking wasn’t just a task but a way of protecting the truth.

“I started as a fact-checker, and it affected me greatly. And I’m so pleased when I see people like my friends at NBC News carefully checking everything, and so frustrated when they’re accused of not doing that,” he said. “Fact-checking is an art, knowing what sources you can trust and what sources you can’t trust.”

Being experienced in the industry, Small has learned a lot about human nature just from experience. He’s seen firsthand that interactions are not always positive, people make mistakes, misremember details, or say the wrong thing under pressure, but that only makes the commitment to accuracy more important.

“Never, ever, ever, ever lose your temper at work. No matter what happens. And don’t gossip about people. If you get into that situation, go home. Go home and say you’re sick. Don’t get mad in the office, and don’t ever burn bridges,” said Small. “You want to keep every person you ever worked with as someone you have a good relationship with because you never know when they are going to be at your next job.”

Small experienced that himself when someone he had crossed paths with in fifth grade unexpectedly reappeared at his next job. While the COVID pandemic forced so many into social isolation, he pushed himself toward creative connection. And he came out of retirement to construct and co-host his podcast, I Couldn’t Throw It Out, an entertaining and nostalgic show where he and fellow Proctor School alum Sally Libby revisit pop culture and history by going through old memorabilia, interviews, and keepsakes collected over decades. Reconnecting with an old friend and collaborating on a creative project again sparked a delightful rediscovery of a version of himself he didn’t want to throw out, either.

“One of the things I discussed on the latest episode is that journalists, especially in the magazine days, would do interviews for an hour, two hours, three hours with celebrities or just interesting people, and the article would use, like, three quotes. And I have these tapes with hours of talking to actors and musicians, and they would just get thrown out. So I’m trying to share those things.”

The podcast became a way to finally give space to the stories that never made it to the final revision, or keepsakes that were left behind. It was about honoring those lost conversations, telling the tales of the meaning behind the objects, and preserving the past before it gets forgotten.

“When I retired, I also realized this huge shock that life has an end. It does not go on forever. I mean, I could be gone tomorrow. Maybe I have another ten years, twenty years, even more, but life has an end,” said Small. “And these boxes, what is going to happen with them? So I realized that I wanted to get rid of it, but I couldn’t get rid of it without sharing it. And so that’s how the podcast happened.”

For Small, the hard part wasn’t the act of throwing things away as much as it was letting go without passing its story on. The podcast became his way of clearing space while documenting the memories behind each possession.

With a willingness to embrace the eclectic stories and resist following trends, Small’s authenticity and creative spirit make him unique compared to many others. He chose to follow his own interests and create something that truly brings him joy and fulfillment, prioritizing passion and keeping memories alive over chasing a greater appeal.

“What I know for sure is that if I were just doing a hip-hop podcast, I would have way more people in the audience. If I were to just do a Swedish death cleaning podcast of all the things I’ve saved personally, I would have way more audience. Or if I just did celebrities, I would have way more audience,” Small said. “But in my typical idiotic way, I don’t want to do that. I want to mix it up. That’s what my life was like. I have fewer audience, but I’m doing what I want to do.”

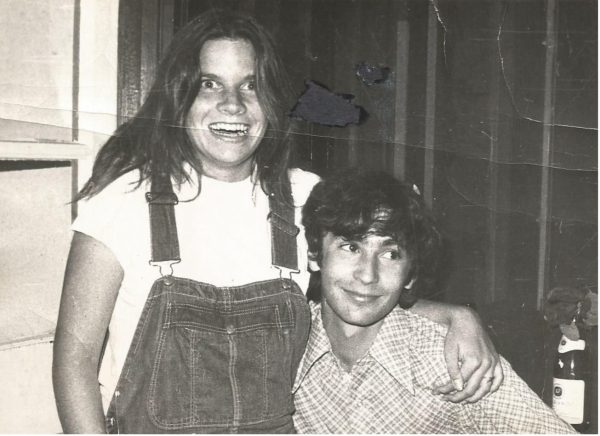

For all the stories he’s told and interviews he’s conducted, it’s the people who have stood by him through it all that remain indispensable. Having maintained friendships dating back about 50 years to his Masco days, Small especially values the support and connections from others, believing that these lasting relationships have encouraged him to take creative risks and embrace new opportunities.

“Your friends are the most important thing in life. And if you can hold on to them, you’re a lucky person,” he said.

Friendship, Small found, often begins in the most unanticipated ways, sometimes starting from uncertainty but growing into something more meaningful than ever. His own story is a perfect example of this unexpected journey.

“Two months after I left Masconomet, I got to college, and I saw this strange-looking woman. I thought, wow, I’m in the wrong school. There are so many weird people here. This is not for me. She spoke English so strangely, she looked like she was about 20 years older, and she was wearing weird clothes. Later on, somebody said, ‘You’re going to really like her.’ I said, ‘No, she’s weird. I don’t want to meet her.’ Anyway, I met her. And she’s my wife now. She’s my inspiration.”

With his passion for telling the stories of others and the objects they leave behind, Michael Small has preserved memories and built meaningful connections lasting decades. Whether through a high school literary magazine, a mainstream news source, or on a podcast about items too sentimental to throw out, he has always found meaning in things others might discard, and continues to make them unforgettable.